Table of contents

Note. The first part of this document has been adapted from Harvard’s CS50’s lecture on Testing.

Unit Tests

Introduction

When writing code, it is common to want to test that your code is working as expected.

- Up until now, you have been likely testing your own code using

printstatements. - Alternatively, you may have been relying upon Ed’s automated testing to test your code for you!

- It’s most common in industry to write code to test your own programs.

In the following, we will use the code below as our example program to be tested. Create a file called calculator.py and modify it as follows:

def square(n):

return n * n

if __name__ == "__main__":

x = int(input("What's x? "))

print("x squared is", square(x))

Notice that you could plausibly test the above code on your own using some obvious numbers such as 2. However, we will show a more systematic way of testing your code.

NOTE

The statement

if __name__ == "__main__":is a common Python idiom that checks whether the script is being run directly or being imported as a module in another script. If the script is run directly, the code block under this statement will execute. If the script is imported as a module, the code block will not execute.

Our First Testing Program

The convention is to separate the testing code from the code being tested. Thus, we will create a new file to test our calculator.py program.

Create a new file named test_calculator.py and modify your code as follows:

from calculator import square

def test_square():

if square(2) != 4:

print("2 squared was not 4")

if square(3) != 9:

print("3 squared was not 9")

if __name__ == "__main__":

test_square()

Notice that we are importing the square function from calculator.py on the first line of code.

If you run test_calculator.py. You’ll notice that nothing is being outputted. It could be that everything is running fine! Alternatively, it could be that our test function did not discover one of the “corner cases” that could produce an error.

Right now, our code tests two conditions. If we wanted to test many more conditions, our test code could easily become bloated. How could we expand our test capabilities without expanding our test code?

Assertions

Python’s assert command allows us to tell the interpreter that something, some assertion, must be true. We can apply this to our test code as follows:

from calculator import square

def test_square():

assert square(2) == 4

assert square(3) == 9

if __name__ == "__main__":

test_square()

Notice that we are definitively asserting what square(2) and square(3) should equal. If either of these assertions is found to be false, the interpreter will stop the execution raising an AssertionError.

Now, our code is shorter!

Let’s purposely break our calculator code by modifying it as follows:

def square(n):

return n + n

if __name__ == "__main__":

x = int(input("What's x? "))

print("x squared is", square(x))

Notice that we have changed the * operator to a + in the square function.

Let’s also add more tests to our test_calculator.py code as follows:

from calculator import square

def test_square():

assert square(2) == 4

assert square(3) == 9

assert square(-2) == 4

assert square(-3) == 9

assert square(0) == 0

if __name__ == "__main__":

test_square()

If we execute test_calculator.py, we will see an AssertionError at the first failed test.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/Users/username/Downloads/test_calculator.py", line 11, in <module>

test_square()

~~~~~~~~~~~^^

File "/Users/username/Downloads/test_calculator.py", line 5, in test_square

assert square(3) == 9

PyTest

pytest is a third-party library that allows you to unit test your program. That is, you can test your functions within your program. It provides more features than simply using assert statements.

To install and use pytest type pip install pytest or pip3 install pytest into your console window.

In the terminal window, type:

pytest test_calculator.py

Pytest will run every function in test_calculator.py that starts with test (any function that does not start with test will be ignored by pytest). You’ll immediately notice that output will be provided.

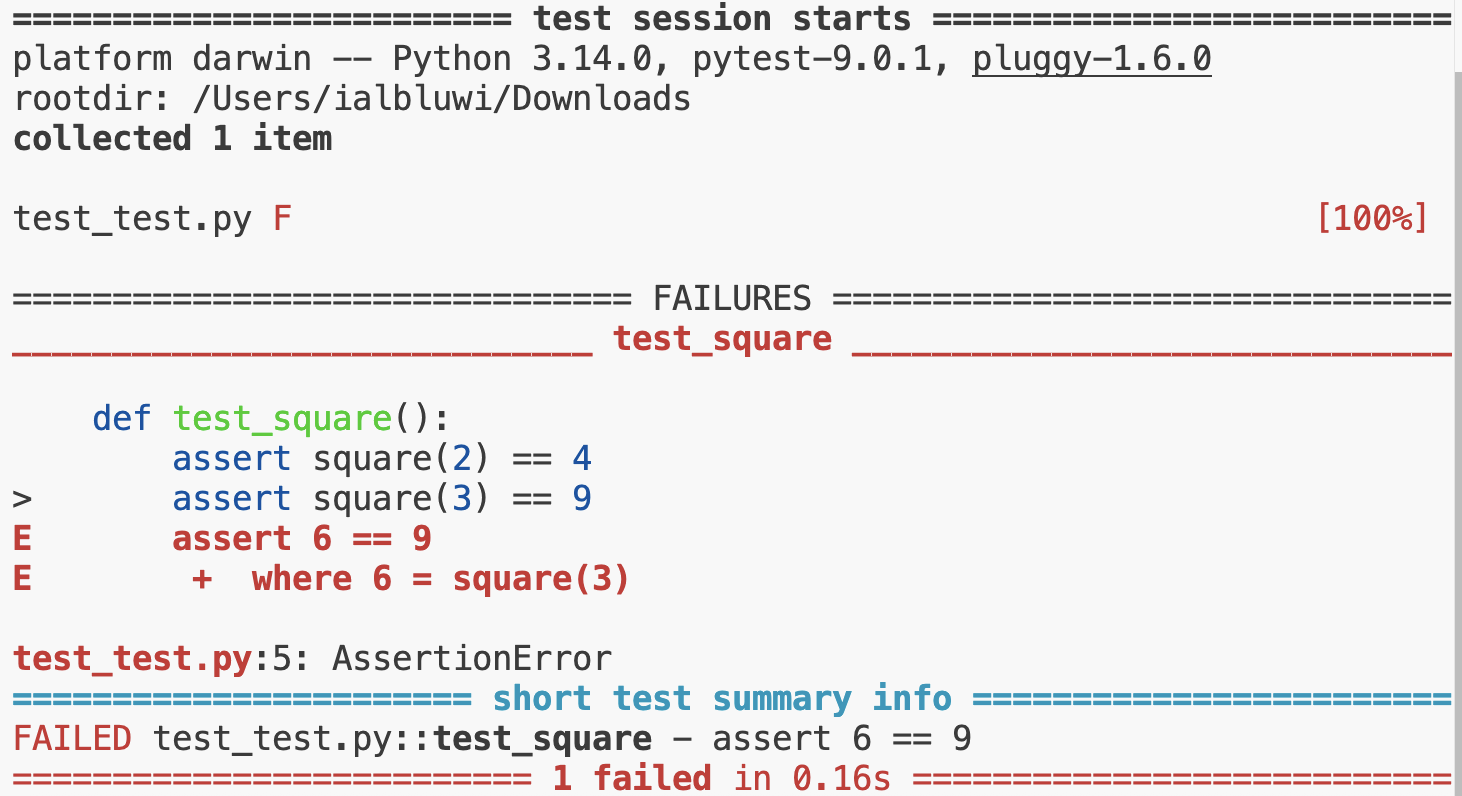

Notice the red F near the top of the output, indicating that something in your code failed. Further, notice that the red E provides some hints about the errors in your calculator.py program. Based upon the output, you can imagine a scenario where 3 * 3 has outputted 6 instead of 9.

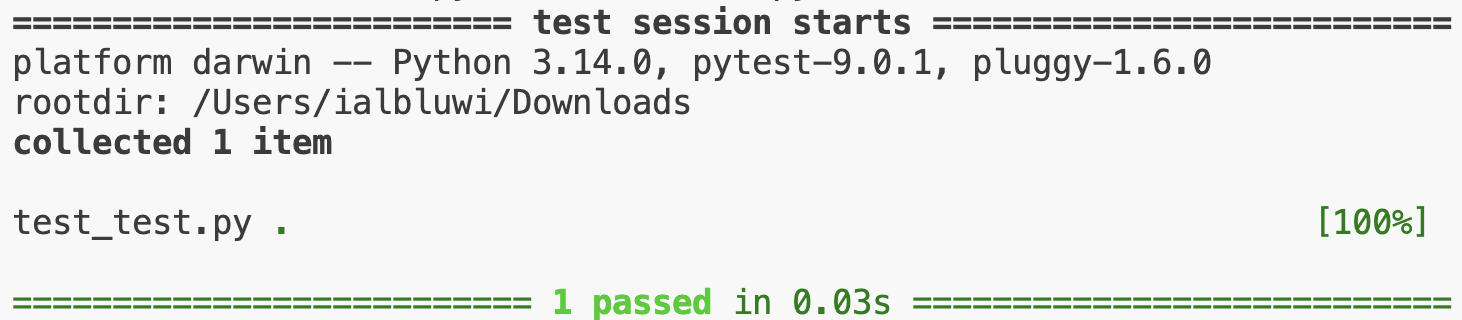

Now, let’s fix the error in our calculator.py and run pytest test_calculator.py again. Notice that no errors are produced. Congratulations!

Organizing Tests

At the moment, it is not ideal that pytest will stop running after the first failed test. This is not ideal. To improve our test code, let’s modify test_calculator.py to divide the code into different groups of tests:

from calculator import square

def test_positive():

assert square(2) == 4

assert square(3) == 9

def test_negative():

assert square(-2) == 4

assert square(-3) == 9

def test_zero():

assert square(0) == 0

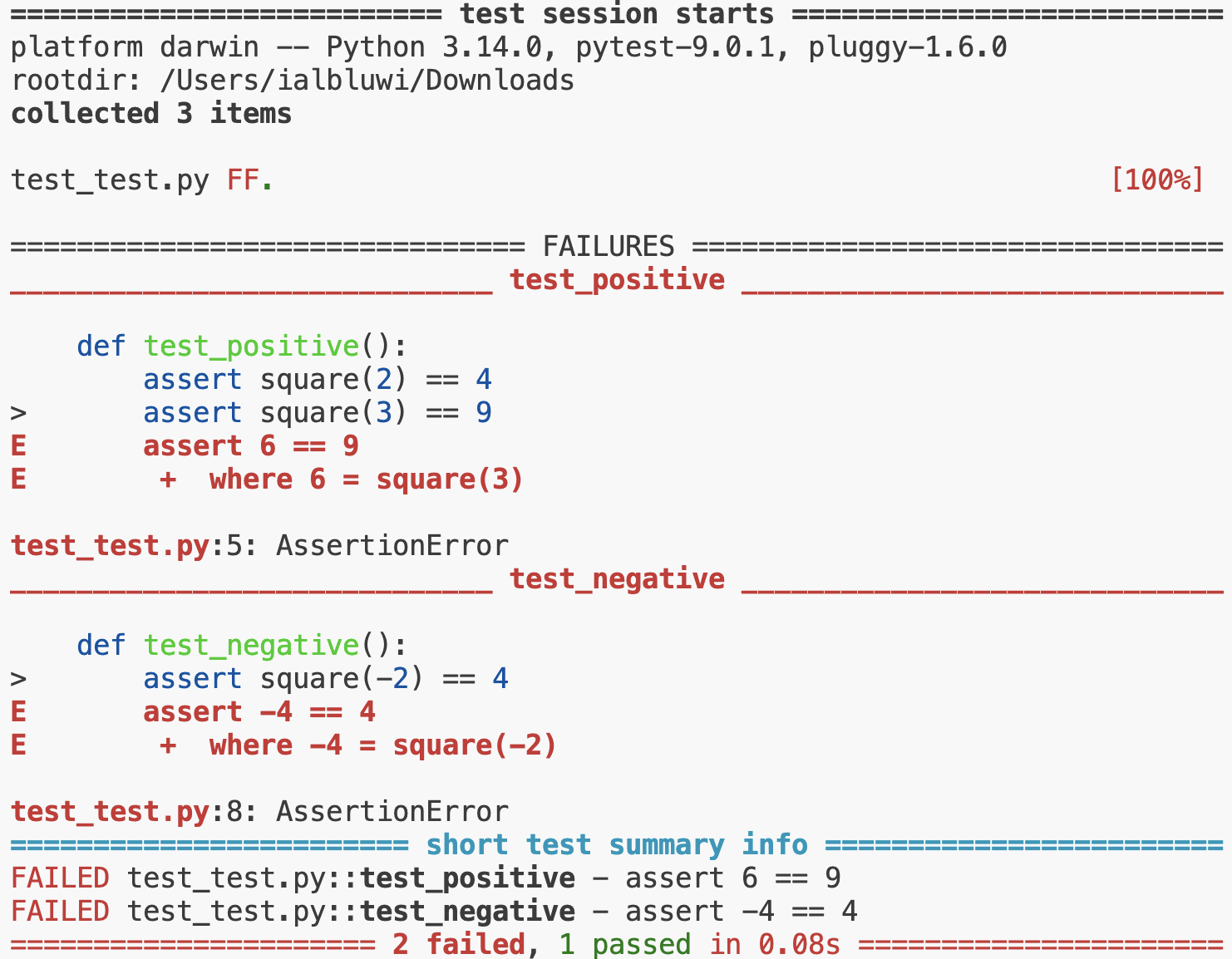

Notice that we have divided the same five tests into three different functions. Testing frameworks like pytest will automatically run each function (without having to write code that calls them). Even if there was a failure in one of functions, pytest still runs all the other functions.

Modify calculator.py back to the buggy code and then run pytest test_calculator.py. You will notice that many more errors are being displayed. More error output allows you to further explore what might be producing the problems within your code.

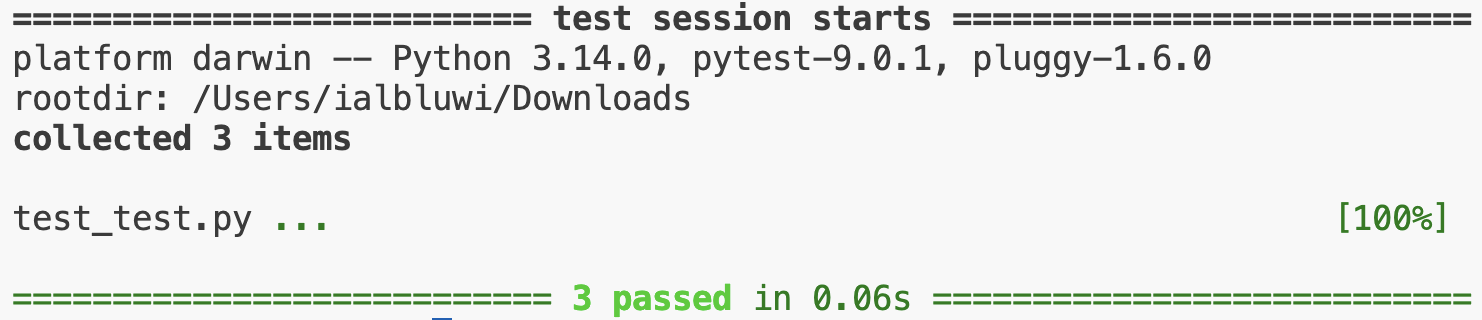

Having improved our test code, return your calculator.py code to fully working order. Re-running pytest test_calculator.py, you will notice that no errors are found.

Testing Strings

Going back in time, consider the following code hello.py:

def hello(to):

print("hello,", to)

if __name__ == "__main__":

name = input("What's your name? ")

hello(name)

Assume that we wish to test the result of the hello function. Consider the following code for test_hello.py:

from hello import hello

def test_hello():

assert hello("David") == "hello, David"

assert hello("world") == "hello, world"

Looking at this code, do you think that this approach to testing will work well? Why might this test not work well? Notice that the hello function in hello.py prints something: That is, it does not return a value!

We can change our hello function within hello.py as follows:

def hello(to):

return "hello, " + to

if __name__ == "__main__":

name = input("What's your name? ")

print(hello(name))

Notice that we changed our hello function to return a string. This effectively means that we can now use pytest to test the hello function.

Running pytest test_hello.py, our code will pass all tests!

Running Tests Automatically

Assume that you have many test files. Typing pytest test_file1.py, pytest test_file2.py, and so forth can be tedious. Instead, you can simply type pytest in the terminal window. pytest will automatically search for all files that start with test_ or end with _test.py and run all of them.

Summary

Testing your code is a natural part of the programming process. Unit tests allow you to test specific aspects of your code. You can create your own programs that test your code. Alternatively, you can utilize frameworks like pytest to run your unit tests for you. In this lecture, you learned about…

Testing & Generative AI

Now that much of the code written by developers is being generated by AI tools, testing has become even more critical.

Writing tests forces you to think critically about what you expect from the code. As you do that, you might notice edge cases or scenarios that you had not considered before. Hence, writing tests helps in two ways:

- It helps you clarify your requirements and expectations for the code.

- It helps you ensure that the generated code meets those expectations.

Example 1

Assume that you’d like to use an AI tool to write a function that counts the number of distinct numbers in a list. You might prompt the AI tool as follows:

Write a Python function called count_distinct

that takes a list of numbers as input and returns

the count of distinct numbers in the list.

The AI tool might generate the following code:

def count_distinct(numbers):

return len(set(numbers))

This code uses set, which we did not cover. Hence, you might not be able to tell if the code is correct simply looking at it. This is a realistic scenario, as even professional developers encounter code that uses concepts or libraries they are not familiar with.

To ensure that this code works as expected, we need to write tests for it. To write effective tests, we should consider various scenarios, including edge cases. Let’s begin by asking the following questions:

In what ways can the input list vary?

Since it is a list of numbers, it can vary in:

- Length.

- Content.

For each of these dimensions, we need to consider different scenarios and cover edge cases. For example:

- Length:

- An empty list.

- A list with one element.

- A list with multiple elements.

- Content:

- All elements are the same.

- All elements are distinct.

- Some elements are repeated.

- Positive, negative, and zero values.

- Duplicates at the beginning, middle, or end of the list.

- Integers and floating-point numbers.

Let’s write tests that cover these scenarios. Create a file named test_count_distinct.py and add the following code (assuming the function is in a file named distinct.py):

from distinct import count_distinct

def test_empty_list():

assert count_distinct([]) == 0

def test_single_element():

assert count_distinct([5]) == 1

def test_all_distinct():

assert count_distinct([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]) == 5

assert count_distinct([5, -1, 4, -2, 0, 8]) == 6

def test_all_same():

assert count_distinct([7, 7, 7, 7]) == 1

assert count_distinct([-3, -3, -3]) == 1

def test_repeated_consecutive():

assert count_distinct([1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 4, 4, -9]) == 5

assert count_distinct([10, 0, 0, 1, 1, 2]) == 4

def test_repeated_non_consecutive():

assert count_distinct([1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 4, 3]) == 4

assert count_distinct([-1, -2, -1, -3, -2, 0]) == 4

def test_first_last_duplicates():

assert count_distinct([1, 1, 0, 2, 5, 9, 9]) == 5

assert count_distinct([-5, 3, 4, -5, 2, 3, -5]) == 4

def test_integers_and_floats():

assert count_distinct([1, 2.0, 3, 2, 1.0, 4.5]) == 4

assert count_distinct([-1.1, -1, -1.0, 0, 0.0]) == 3

The above tests are organized into separate functions. This organization helps in identifying which specific scenario fails if an error occurs. Remember that if we jot all the tests together in one function, a failure in one test would prevent the execution of subsequent tests, making it harder to identify all issues at once.

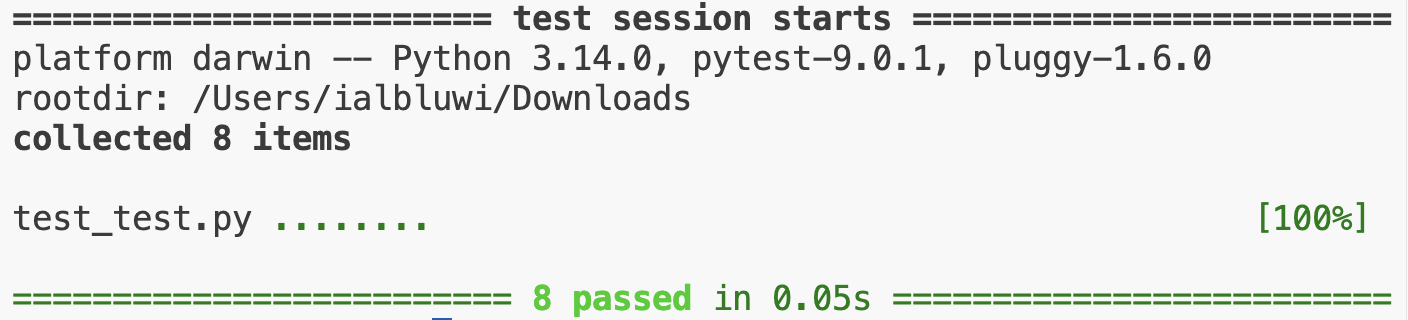

Let’s run the tests using pytest:

We can comfortably now move forward knowing that our count_distinct function works as expected across a variety of scenarios.

A great benefit of having these tests is that if we ever need to modify the function in the future, we can re-run these tests to ensure that our changes do not introduce any new bugs. This is an important aspect of software development, especially when working with large codebases or when multiple developers are involved. In such situations, modifying code can inadvertently break other pieces of the code that depend on it. Having a comprehensive suite of tests helps catch such issues early.

Example 2

Let’s use an AI tool to write a function that checks if two strings are anagrams of each other. Two strings are anagrams if they contain the same characters in a different order. We might prompt the AI tool as follows:

Write a Python function called are_anagrams

that takes two strings as input and returns

True if they are anagrams of each other,

and False otherwise.

The AI tool might generate the following code:

def are_anagrams(str1, str2):

str1 = str1.replace(" ", "").lower()

str2 = str2.replace(" ", "").lower()

str1 = ''.join(char for char in str1 if char.isalnum())

str2 = ''.join(char for char in str2 if char.isalnum())

if len(str1) != len(str2):

return False

char_count = {}

for char in str1:

char_count[char] = char_count.get(char, 0) + 1

for char in str2:

if char not in char_count:

return False

char_count[char] -= 1

if char_count[char] < 0:

return False

return True

This code is relatively long and uses Python syntax we did not cover in class! The more complex the code, the more important it is to write tests to ensure its correctness.

Without understanding the code, we can design test cases to check if it works as intended or not. Let’s think about how the input strings can vary:

- Length:

- Both strings are empty.

- One string is empty, and the other is not.

- Both strings have the same length.

- Both strings have different lengths.

- Content:

- Both strings are identical.

- Both strings are anagrams of each other.

- Both strings are not anagrams of each other.

- Strings with spaces and different cases.

Let’s write tests that cover these scenarios. Create a file named test_anagrams.py and add the following code (assuming the function is in a file named anagrams.py):

from anagrams import are_anagrams

def test_empty_strings():

assert are_anagrams("", "") == True

def test_one_empty_string():

assert are_anagrams("", "abc") == False

assert are_anagrams("abc", "") == False

def test_identical_strings():

assert are_anagrams("listen", "listen") == True

def test_anagram_strings():

assert are_anagrams("listen", "silent") == True

assert are_anagrams("Astronomer", "moonstArer") == True

assert are_anagrams("Dormitory", "Dirtyroom") == True

assert are_anagrams("$$$###", "#$#$#$") == True

def test_non_anagram_strings():

assert are_anagrams("hello", "world") == False

assert are_anagrams("abc", "def") == False

assert are_anagrams("abcd", "aabbccdd") == False

assert are_anagrams("hello there", "hello, there!") == False

assert are_anagrams("test", "tEsts") == False

assert are_anagrams("$#", "#$#$") == False

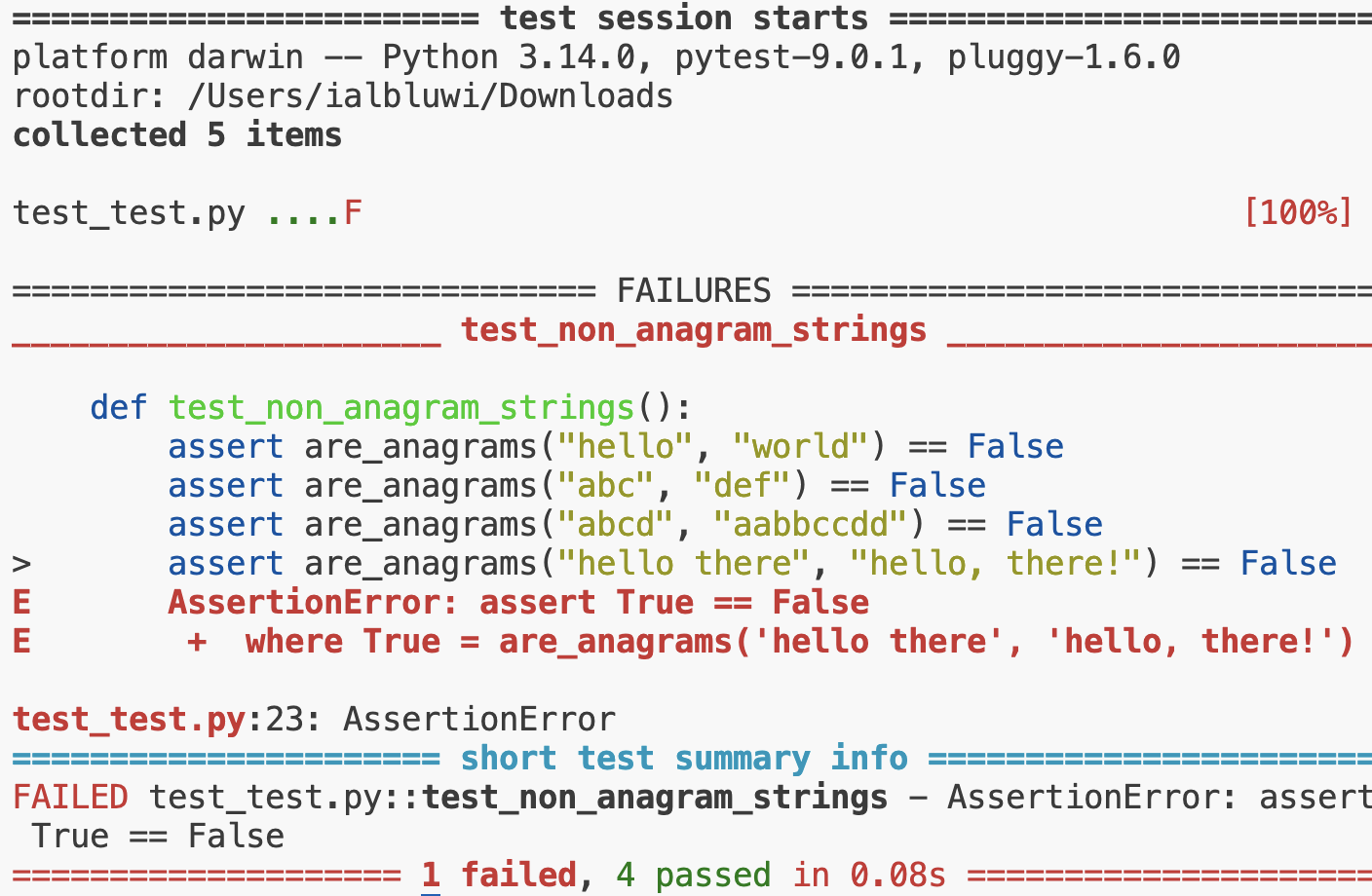

Let’s run the tests using pytest:

Unfortunately, one of our tests failed. The test that failed is the one checking if are_anagrams("hello there", "hello, there!") returns False. Our assumption is that the function should not ignore punctuation, whitespaces, and cases. However, we did not mention this in our prompt to the AI tool. It seems that the AI tool assumed that we wanted to ignore these factors. This is a reasonable assumption. It is our fault for not being specific enough in our prompt.

Luckily, we have tests that caught this issue! Let’s rewrite our prompt to be more specific:

Write a Python function called are_anagrams

that takes two strings as input and returns

True if they are anagrams of each other, and

False otherwise. The function should consider

spaces, punctuation, and case sensitivity when

determining if the strings are anagrams.

For example, "Listen" and "Silent" should not

be considered anagrams because of the case

difference. Similarly, "hello there" and

"hello, there!" should not be considered

anagrams due to the punctuation and space

differences.

The AI tool might generate the following revised code:

def are_anagrams(str1, str2):

return sorted(str1) == sorted(str2)

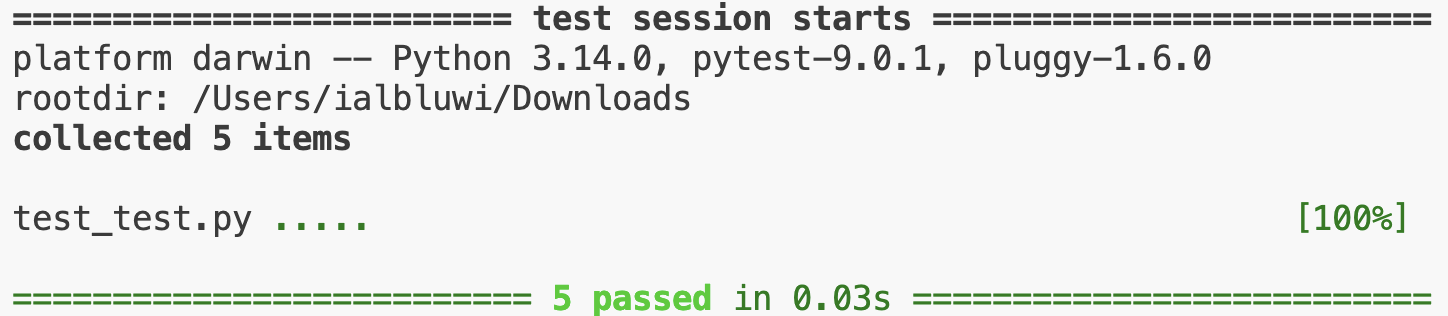

Now the code is much shorter! Would this code pass all our tests? Let’s run pytest test_anagrams.py again:

All tests pass successfully!

Summary

When using AI tools, it is crucial to use precise and detailed prompts. One effective way to ensure that your prompts are precise is to write tests that cover various scenarios and edge cases. Writing tests helps clarify your requirements and expectations for the code, ensuring that the generated code meets those expectations.