Data Representation (Part 1)

Table of contents

Bits, Bytes, Kilobytes, etc.

A bit is the smallest unit of data in a computer. It can have a value of either 0 or 1. The term bit is short for binary digit.

Typically, bits are grouped together to form larger units of data. The most common grouping is the byte, which consists of 8 bits. Below is a breakdown of common data size units:

1 Bit = A single binary digit (0 or 1)

1 Byte (B) = 8 bits

1 Kilobyte (KB) = 1,024 Bytes

1 Megabyte (MB) = 1,024 Kilobytes ≈ 1 Million Bytes

1 Gigabyte (GB) = 1,024 Megabytes ≈ 1 Billion Bytes

1 Terabyte (TB) = 1,024 Gigabytes ≈ 1 Trillion Bytes

Possible Values with Bits

With 1 bit, we can represent 2 possible values: 0 and 1.

With 2 bits, we can represent 4 possible values:

00

01

10

11

With 3 bits, we can represent 8 possible values:

000

001

010

011

100

101

110

111

As you can see, each additional bit doubles the number of possible values. Therefore, with \(n\) bits, we can represent \(2^n\) possible values. Hence, with 1 byte (8 bits), we can represent \(2^8 = 256\) possible values, ranging from \(0\) to \(255\).

How many bits are needed?

Let’s consdier the following number of bits and their range of possible values:

# of Bits Range of Possible Values

--------- ------------------------

1 2^1 = 2 (0 to 1)

2 2^2 = 4 (0 to 3)

3 2^3 = 8 (0 to 7)

4 2^4 = 16 (0 to 15)

5 2^5 = 32 (0 to 31)

6 2^6 = 64 (0 to 63)

7 2^7 = 128 (0 to 127)

8 2^8 = 256 (0 to 255)

Let’s assume we want to store the number \(6\) on a computer. How many bits do we need? Since \(6\) in binary is 110, we need at least 3 bits. We can also use 4 bits: 0110, 5 bits: 00110, 6 bits: 000110, or more, but the minimum is 3 bits.

How many bits are need to store the number 2025? This is not clear from the table above.

Given a number of bits \(n\), we can store numbers from \(0\) to \(2^n - 1\). Hence, we need to find the smallest \(n\) such that:

\[2025 \leq 2^n - 1 \longrightarrow 2025 + 1 \leq 2^n\]Taking the base-2 logarithm of both sides:

\[\log_2(2026) \leq n\]Using a calculator, we find that \(\log_2(2026) \approx 10.98\). Since \(n\) must be an integer, we round up to the next whole number, so \(n = 11\). This means we need at least 11 bits to store the number 2025.

FORMULA

The number of bits needed to represent a positive integer \(x\) is given by:

\[\textrm{bits} = \lceil \log_2(x + 1) \rceil\]where \(\lceil \cdot \rceil\) denotes the ceiling function, which rounds up to the nearest integer.

Represnting Text

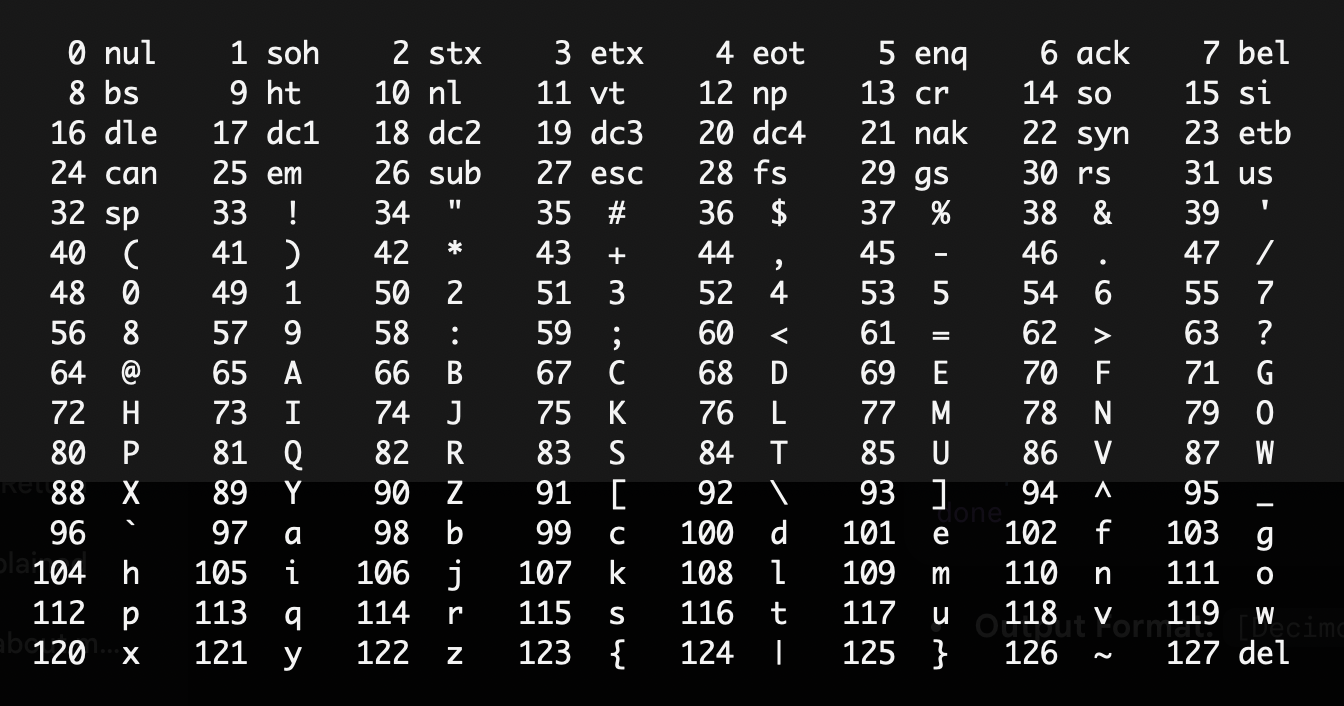

Since we can’t directly store letters and characters on a computer, we store them as numbers. One common way to do this is using the ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) encoding system. In ASCII, each character is assigned a unique number between 0 and 127. For example:

As you can see from the table above:

Ais represented by the number 65.Bis represented by the number 66.ais represented by the number 97.bis represented by the number 98.0is represented by the number 48.1is represented by the number 49.- The space character ` ` is represented by the number 32.

How many bits are needed to represent all ASCII characters? Since the highest ASCII value is 127, we can use our formula:

\[\textrm{bits} = \lceil \log_2(127 + 1) \rceil = \lceil \log_2(128) \rceil = \lceil 7 \rceil = 7\]Thus, we need at least 7 bits to represent all ASCII characters. However, in practice, we often use 1 byte (8 bits) to store each ASCII character, leaving one bit unused.

File Sizes

Example 1: Open a new empty file in VS Code and type: ABCD. Save the file as abcd.txt.

Now, check the size of the file. You should see that the file size is 4 bytes. This is because each character (A, B, and C, D) is stored using 1 byte each.

Example 2: Modify the contents of the file to be: أبجد Save the file again and check its size. You might be surprised to see that the file size is now 8 bytes.

Since ASCII only supports English letters and some special characters, the Arabic letters are stored using a different encoding system called UTF-8. In UTF-8, each Arabic character is represented using 2 bytes. Therefore, the 4 Arabic letters أ, ب, ج, and د require a total of 8 bytes.

Example 3: Replace the Arabic letters with emojis, such as: 😀😃😄😁. Save the file and check its size. You will find that the file size is now 16 bytes. The reason is that emojis are represented using 4 bytes each in UTF-8 encoding. Therefore, the 4 emojis require a total of 16 bytes.

Fun with Python

Open a Python interactive shell (REPL) and type the following commands:

ord('A') # returns 65

ord('ب') # returns 1576

ord('😀') # returns 128512

The ord() function in Python returns the corresponding numeric value of a character based on its encoding.

Now try the following:

chr(65) # returns 'A'

chr(1576) # returns 'ب'

chr(128512) # returns '😀'

The chr() function in Python returns the character corresponding to a given numeric value based on its encoding.

Putting it all together, what does the following function do?

from random import randint

def mystery():

r = randint(128511, 128591)

print("Hello", chr(r))

Representing Floating-Point Numbers

The actual representation of floating-point numbers in computers is quite complex and involves a standard called IEEE 754, which is beyond the scope of this course. Instead, we will discuss how to convert decimal (floating-point) numbers to binary. This will reveal some of the challenges involved in representing floating-point numbers.

Representing the Fractional Part

We already know that a binary number like 1011 represents in decimal:

However, what does the binary number 0.1011 represent in decimal?

The idea is the same, but instead of powers of 2, we use powers of \(\frac{1}{2}\) (or negative powers of 2):

\[\begin{aligned} 0.1011_2 & = (1 \times 2^{-1}) + (0 \times 2^{-2}) + (1 \times 2^{-3}) + (1 \times 2^{-4}) \\ & = \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \frac{1}{2}\ \ \ \ \ \ + \ \ \ \ \ \ 0\ \ \ \ \ \ \ + \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \frac{1}{8} \ \ \ \ \ + \ \ \ \ \ \ \frac{1}{16}\\ & = \ \ \ \ \ \ \ 0.5\ \ \ \ + \ \ \ \ \ \ 0\ \ \ \ \ \ \ +\ \ \ \ \ 0.125\ \ +\ \ \ 0.0625 \\ & = 0.6875 \end{aligned}\]Thus, 0.1011 in binary is equal to 0.6875 in decimal.

Given a binary number with both integer and fractional parts, such as 110.101, we can convert it to decimal by separating the two parts and converting each part individually.

Converting a Decimal Fraction to Binary

To convert a decimal fraction to binary, we can use the following method:

- Multiply the decimal fraction by 2.

- The integer part of the result (0 or 1) becomes the next binary digit.

- Take the fractional part of the result and repeat steps 1-3 until you reach the desired precision or the fractional part becomes 0.

Example 1: Convert 0.625 to binary.

0.625 * 2 = 1.25 -> Integer part: 1

0.25 * 2 = 0.5 -> Integer part: 0

0.5 * 2 = 1.0 -> Integer part: 1

Reading the integer parts from top to bottom, we get 0.101 in binary. Thus, 0.625 in decimal is equal to 0.101 in binary.

Example 2: Convert 27.8125 to binary.

- Convert the integer part

27to binary:27 / 2 = 13 remainder 1 13 / 2 = 6 remainder 1 6 / 2 = 3 remainder 0 3 / 2 = 1 remainder 1 1 / 2 = 0 remainder 1Reading the remainders from bottom to top, we get

11011in binary. - Convert the fractional part

0.8125to binary:0.8125 * 2 = 1.625 -> Integer part: 1 0.625 * 2 = 1.25 -> Integer part: 1 0.25 * 2 = 0.5 -> Integer part: 0 0.5 * 2 = 1.0 -> Integer part: 1Reading the integer parts from top to bottom, we get

0.1101in binary.

Combining both parts, we get 27.8125 in decimal is equal to 11011.1101 in binary.

Surprises with Floating-Point Numbers

Open a Python interactive shell (REPL) and type the following commands:

print(0.1 + 0.2 == 0.3) # Expected output: True

print(0.1 + 0.2) # Expected output: 0.3

You might be surprised to see that the first line outputs False, and the second line outputs 0.30000000000000004 instead of 0.3.

This happens because some decimal fractions cannot be represented exactly in binary, leading to small rounding errors in floating-point arithmetic. This is a common issue in computer programming and numerical computing.

Let’s try converting 0.1 to binary using the method we discussed earlier:

0.1 * 2 = 0.2 -> Integer part: 0

0.2 * 2 = 0.4 -> Integer part: 0

0.4 * 2 = 0.8 -> Integer part: 0 <----

0.8 * 2 = 1.6 -> Integer part: 1

0.6 * 2 = 1.2 -> Integer part: 1

0.2 * 2 = 0.4 -> Integer part: 0

0.4 * 2 = 0.8 -> Integer part: 0 (repeats)

0.8 * 2 = 1.6 -> Integer part: 1

0.6 * 2 = 1.2 -> Integer part: 1

0.2 * 2 = 0.4 -> Integer part: 0

0.4 * 2 = 0.8 -> Integer part: 0 (repeats)

...

As you can see, the process will continue indefinitely, producing a repeating pattern. Therefore, 0.1 cannot be represented exactly in binary, leading to the small error we observed in Python.

Floating-Point Comparison

When comparing floating-point numbers, it’s often better to check if they are “close enough” rather than exactly equal. Otherwise, you might encounter unexpected results due to the representation issues we discussed.

Here is a common approach to compare floating-point numbers:

from math import isclose

a = 0.1 + 0.2

b = 0.3

print(a == b) # Output: False

print(isclose(a, b)) # Output: True

The isclose() function checks if two floating-point numbers are the same up to nine decimal places (by default), which helps avoid issues with tiny representation errors.